Mediterranean Garden Society

Mediterranean Garden Society

Propagation from cuttings

The photograph at the top of this page shows nodal and internodal cuttings ready to go into potting medium (Photo Priscilla Worsley)

Making plants from plants is a subject close to most gardeners’ hearts, and here in the mediterranean-climate areas we are no different. Our green-fingered friends seem to know by instinct how best to break off a piece of an interesting plant and make it grow, but the rest of us need guidance. MGS members and garden designers Jennifer Gay and Piers Goldson give the basic information about the taking of cuttings. A commercial rose grower then reveals his way with traditional roses.

Propagating in the Mediterranean

by Jennifer Gay and Piers Goldson – notes from a workshop held at Sparoza for the 2007 MGS AGM Symposium

Traditional rose varieties - propagation from cuttings

Lecture by Yan Surguet at the Rose Festival, Château de Flaugergues in October 2010, reported by Chantal Guiraud

For additional reports and articles on this subject please check out the (non-responsive) MGS Archive.

Propagating in the Mediterranean

Jennifer Gay and Piers Goldson are both past Garden Assistants at Sparoza and have gone on to be successful garden designers in Greece. At the MGS Symposium in Athens in November 2007, they gave a workshop on propagation and here is the part of their notes concerning propagation from cuttings, including layering:

An introduction to taking cuttings

Any material selected for vegetative propagation must be true to type, free from pests and diseases and not flowering. If flowering material is selected all flower buds must be removed as the plant will use energy to produce them rather than develop a new root system.

It is important that the medium for rooting cuttings is firm and dense so it will hold the cuttings upright, and it must retain enough moisture not to need constant watering. Commonly used mixes for cuttings are:

Cuttings can be treated with a rooting hormone (auxin) to increase their propensity to form roots, to hasten root initiation and to increase the uniformity of rooting. Plants that root easily do not benefit from an extra supply of auxin, and it is best to save rooting hormones for those that are difficult to root.

1. Root Cuttings

Some perennials with fleshy roots are propagated from root cuttings taken in the dormant season. Lift the plant, and after cutting off a few strong, healthy, pencil-thick roots, replant the mother plant. Use the smaller lateral roots. Cut across the top at a right angle and trim the bottom at a slanting angle to give a larger surface from which the new roots can develop. This will also help you distinguish top from bottom. Cuttings to be raised in the open should measure at least 10 cm while those kept under protection can be 5 cm. Before inserting the cuttings into gritty compost, it is advisable to dust the surfaces with a fungicide; there is no need for rooting hormone. The tip of the cuttings should be level with the compost and covered with one centimetre of gravel.

Keep the cuttings dry to prevent them from rotting. Root cuttings can also be taken from woody plants which have a tendency to sucker from the roots such as Albizia, Aralia, Catalpa, Chaenomoles, Populus and Robini. Acanthus mollis and perennial poppies also propagate successfully with this method.

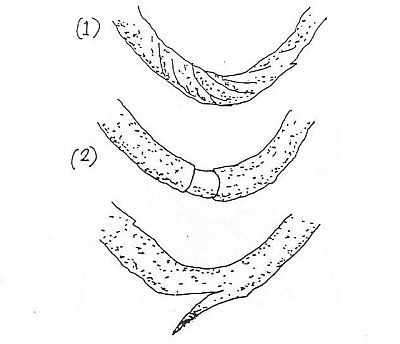

Select small lateral roots for cuttings. When cutting the roots, trim each section straight across the top and slanting at the base in order to distinguish the top from the bottom (1). Insert the cuttings into compost the correct way up so that the top is level with the surface. Cover the compost with a 1 cm layer of gravel (2).

2. Softwood Cuttings

Spring and autumn are the time to take softwood cuttings of shrubs and perennials. Choose young vigorous growth that is still soft and green and will root without too much difficulty. Because softwood cuttings wilt very quickly, put them in a plastic bag and keep them in a cool place if you are unable to set them in compost straight away.

There are two types of softwood cuttings, nodal and internodal:

2.1. Nodal Cuttings

Nodal cuttings take the soft tip just below a leaf node. Look for strong new growth with a healthy leaf bud at the end (not a fat flower bud). If you have never taken cuttings before start with something easy like sage (Salvia officinalis). With a sharp knife cut just below a leaf joint or node and remove the lower leaves. You can dip the base in a rooting hormone powder although cuttings often root just as well without. A fungicidal dip is a useful precaution, or remove wilting or rotting material as soon as it becomes obvious. Insert the cuttings round the edges of a pot of freely draining compost such as one part compost to one or two parts sharp sand. Generally less commonly used than semi-ripe and hardwood cuttings in colder climes, softwood cuttings are easier in the Mediterranean. Try Hebe, Lonicera, Philadelphus, Parthenocissus, Perovskia, Pyracantha and Wisteria with this method.

Gather softwood cuttings early in the morning and have everything ready in advance so you can insert them without delay. Trim the stem just below a leaf joint (here Pelargonium) and remove the lower leaves from the cutting (1). Insert the cuttings in sandy compost (2) (stand the pot in water first so that it is thoroughly moist).

2.2. Internodal Cuttings

Internodal cuttings are used for plants such as Buddleja davidii that have a lengthy stem between the leaf joints (known as a large internodal spacing). The cut is made at a point roughly half-way between two nodes. Internodal propagation allows the cutting to shoot from the base rather than develop a short stem.

This technique is used for climbing plants with a lengthy stem between the leaf joints or internodes. Trim above a leaf joint and insert about 2-3 cm of stem in gritty compost. Remove some of the leaves to cut down on water loss.

3. Semi-Ripe Cuttings

Shrubs, trees and climbers including evergreens are often propagated from semi-ripe cuttings in late summer (or from hardwood cuttings taken during the winter months – see below). Take semi-ripe cuttings when the new season’s growth starts to harden towards the end of the growing season. Box, cypress, Eleagnus, juniper, jasmine, Nandina, Pittosporum and Trachelospermum are among the species which are commonly propagated this way. Cut terminal growths with all the current season’s growth in late summer, 10-15 cm long. Remove leaves from the lower half of the stem so they do not come into contact with the compost. Because the stems have begun to produce bark some semi-ripe cuttings may require wounding. Make a flat cut below a node. If the bark is thick wound the specimen then dip the base in rooting hormone and insert into soil or gritty compost, topped with a 2.5 cm layer of sharp sand, in a shaded protected place. To reduce water loss and save space, cut large leaves like cherry laurel (Prunus laurocerasus) in half.

Trim the stem immediately below a leaf joint (here Choisya) and remove the lower leaves from the cutting (1). Dip the base of the cutting in rooting hormone powder and remember to tap off any excess. Insert the cutting through the layer of sharp sand so that the base of the stem sits just below the surface of the compost.

A number of conifers and evergreens will root more reliably if cuttings are taken with a heel. This means pulling side shoots from the main stem so they come off with a small strip of old wood known as a heel.

Pull off a young side shoot (here rosemary) in such as way that a strip of the previous year’s growth is attached (1). Trim off the ragged tail of the heel, dip in rooting hormone powder, remembering to tap off any excess, and insert in gritty compost (2).

4. Hardwood Cuttings

Easy subjects for a first experiment with hardwood cuttings are dogwood (Cornus), poplar, plane, Hibiscusand Weigela. The aim is to induce the cutting to produce roots before the buds grow in spring. In winter just after leaf fall, cut lengths of hardened woody stem bearing at least three buds. Trim the bottom end at an angle and the top end level, just above a bud. Insert the cuttings into a V-shaped trench in open ground leaving the top buds showing and firm them in. In heavy clay mix some sharp sand into the soil and also place some at the base of the trench to ensure good drainage.

5. Layering

Many shrubs and climbers can be propagated by layering. This method differs from other methods of vegetative propagation in that the new addition is induced to produce roots while it is still attached to the parent plant. Once rooted this new plant is then severed from its parent and allowed to grow on its own roots unaided. This method of propagation produces a much larger plant in a shorter time compared with other methods of propagation. The easiest plants to produce by this method are those that naturally produce suckers. Many, such as blackberry, naturally reproduce themselves by this method.

Climbers are also easily reproduced by layering, with Jasminum making an especially good subject. During the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries layering was widely used and often was the primary method of propagation due to the fact that it costs nothing.

Constriction must be induced within the stem to restrict the natural flow of auxin which acts as a rooting hormone at the point of restriction. The exclusion of light is thought to speed up the production of wound tissue and hence increase the speed of rooting.

In autumn, late winter or early spring select a strong new stem that will reach down to ground level and prepare the soil at this point by forking in garden compost and grit. Pull down the stem and constrict it to encourage root formation, either by making a slanting cut a third of the way through, twisting the stem or girdling it. Peg the cut branch down into the prepared soil with the end tied vertically to a stake. Water in dry weather. The developing layer may produce sufficient root growth by early summer, though sometimes it takes a year or two. Sever the layer as close to the parent plant as possible, and after four to six weeks carefully lift it. The layer can either be placed in its permanent position, or containerized and grown on.

This is a reliable method of propagating shrubs with low-growing branches such as magnolias, Photinia, bay and lilac. Climbers can be increased by pulling down a long shoot, wounding the stem and pegging it down.

Twisting is achieved by rotating each end of the stem in opposite directions and pinning down.

Girdling involves removing the top layer of bark, as shown, with a sharp knife.

Create a wound or ‘tongue’ by making an incision into a third of the thickness of the stem.

Traditional rose varieties - propagation from cuttings

Part of a lecture by Yan Surguet at the Rose Festival, Château de Flaugergues, in October 2010, reported by Chantal Guiraud

Yan Surguet, a qualified landscape architect, is one of the leading producers of traditional rose varieties. All his stock has an organic certification and is propagated from cuttings. His nursery, Jardin de Talos, is located in the Ariège, at Taurignan-Vieux, south of Toulouse, but he also attends some plant fairs.

Why propagate roses from cuttings?

This is the only way to ensure that the new plant keeps its genetic origin. Unlike grafted roses, suckers are never produced. The shoots that are sometimes thrown out from roses produced by cuttings are in fact identical to the original variety and do not weaken the plant. Grafted roses, such as Gallica, Alba, Moss, Damask or Cabbage roses can be beautiful for a few years, but generally deteriorate after ten years if they have had their suckers removed (suckering is a natural habit which helps the plant survive). Gallica, Alba, Moss and Cabbage roses send out a lot of suckers whereas Musk, Bourbons and Multiflora do not sucker, regardless of whether they come from cuttings or from grafted stock. Rose suppliers often graft on to rootstock as this is more cost-effective for them, success being more reliable than with cuttings. Most cuttings take eventually but may take more time. Roses grafted on to Rosa multiflora rootstock almost never sucker, unlike those grafted on to Rosa canina.

Propagation of organically cultivated roses

Cuttings are taken in the autumn from stock plants which have been cultivated in the ground for over 30 years without the use of fertilizers or pesticides. The cutting, about the size of a pencil, is potted in a mixture of loam and horticultural compost without using rooting hormones.

Potting mixture:

* Volcanic material (pumice or volcanic ash) also known as pozzolana, predominantly composed of fine volcanic glass.

This is quite a heavy mixture, but will produce strong plants which should recover well when planted out. The pots are placed against a north-facing wall and the young plants allowed to develop in the open air, without the addition of heat, light, fertilizer or pesticides. This ensures a more resistant plant, whose growth and flowering have not been forced and which should survive the transfer to garden conditions without problems.

The pots are watered sparingly and after 4 to 6 months the first leaves appear. The young plant can then be transplanted into a bigger pot and planted in the ground in the autumn.

THE MEDITERRANEAN GARDEN is the registered trademark of The Mediterranean Garden Society in the European Union, Australia, and the United States of America